1. Unix and shell commands¶

Tcsh shell commands, Unix commands and special key strokes

Note

for getting help in Unix, try the “manual” pages: man COMMAND

Shell commands are particular to the shell (tcsh, in this case).

Unix commands are common to all Unix systems, though options vary a bit.

Special characters may apply to Unix in general, or be particular to a shell.

1.1. Shell Commands¶

A shell command is one that is processed internally by the shell. There is no corresponding executable program.

Take cd for instance. There is no /bin/cd program, say, and which cd specifies that it is a built-in command. It is part of the shell. The cd command is processed by the shell (tcsh or bash, say).

Contrast that with ls. There is a /bin/ls program, as noted by which ls. The shell does not process ls internally.

See also

for getting help from the shell, use man, e.g.

man tcsh

man bash

1.1.1. bg¶

put the most recently accessed job (child process) in the background

This is most commonly entered after ctrl-z. One might also use the output of jobs, and specify a job number.

See also

man tcsh

1.1.2. cd¶

change directories

The cd command is used to change directories. Without any parameters, the shell will change to the user’s home directory ($HOME). Otherwise, it will change to the single specified directory.

Examples:

cd cd $HOME cd suma_demo cd AFNI_data6/FT_analysis cd ~username cd /absolute/path/to/some/directory cd relative/path/to/some/directory cd ../../some/other/dir

Since .. is the parent directory, including such entries will travel up the directory tree.

Note

It is a good idea to follow a cd command with ls to list the contents of the new directory.

See also

man tcsh

1.1.3. echo¶

echo text to the terminal window

The echo command displays the given text on the terminal window. This is often used to show the user what is happening or to prompt for a response. There are more devious uses, of course…

Examples:

echo hello there echo "this section performs volume registration" set my_var = 7 echo "the value of my_var = $my_var"

See also

man tcsh

1.1.4. fg¶

put the most recently accessed job (child process) in the foreground

This is most commonly entered after ctrl-z. One might also use the output of jobs, and specify a job number.

While bg keeps a process running, but leaves the terminal window available for new commands, fg puts a process in the foreground, so commands would no longer be available.

See also: bg

See also

man tcsh

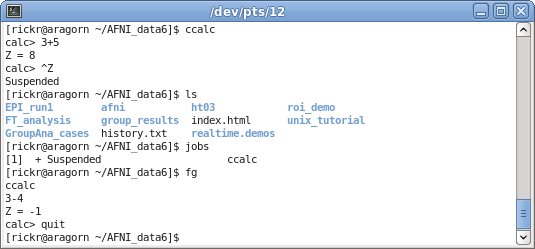

1.1.5. jobs¶

list processes started from current shell

The jobs command lists processes that have been started from the

current shell (the current terminal window, probably) that are either

suspended or running in the background. Processes are suspended via

ctrl-z, and can then be put into the background using the 'bg’

command (or by using & in the first place).

Examples:

jobs - probably shows nothing

See also

man tcsh

the example from: ctrl-z

1.1.6. set¶

assign a value to a shell variable

The set command assigns a value to a variable (or multiple values to multiple variables). Without any options, all set variables are shown.

If a value has spaces in it, it should be contained in quotes. If a list of values is desired, parentheses () should be used for the assignment, while indivisual access is done via square brackets [].

Examples:

set set value = 7 set new_val = "some number, like seven" echo $new_val set list_of_vals = ( 3 1 4 one five ) echo $list_of_vals echo $list_of_vals[3] set path = ( $path ~/abin )

Note

A single set command can be used to set many variables, but such a use is not recommended.

Note

- set is for setting shell variables, which do not propagate

to child shells. To propagate to a child shell, use environment variables. A child shell would be created when a new shell is started, such as when running a script.

setenv DYLD_FALLBACK_LIBRARY_PATH $HOME/abin

See also

man tcsh

1.1.7. setenv¶

set an environment variable

The setenv command works like ‘set’, except that if a child shell is started (such as when running a script), the environment variables are preserved. Note that environment variables are generally in all caps by convention, to visually distinguish them from regular shell variables.

Lists are assigned using the bash-like syntax of ‘:’ delimited elements, rather than with ‘()’ and space delimited elements as ‘set’ uses. When a list is added to, as with the $PATH example, the variable should be within ‘{}’, so that the ‘:’ does not look like a modifier (i.e. using ${PATH} rather than just $PATH).

Examples:

setenv MY_ENV_VAR "some value" setenv PATH ${PATH}:$HOME/abin setenv DYLD_FALLBACK_LIBRARY_PATH $HOME/abinExamples of similar commands using bash:

name="Maria Buttersworth" export name export name="Maria Buttersworth" export DYLD_FALLBACK_LIBRARY_PATH=$HOME/abin

For more help, see man tcsh.

1.1.8. unset¶

delete a shell variable

This does not just clear the variable, but makes it “not exist”.

Examples:

set value = 7 echo $value unset value echo $valueThe result of the last

echo $valuecommand would produce an error, since that variable no longer exists.

1.1.9. unsetenv¶

delete an environment variable

This does not just clear the variable, but makes it “not exist”.

Examples:

unsetenv DYLD_FALLBACK_LIBRARY_PATH unsetenv AFNI_NIFTI_DEBUG

See also

1.2. Unix Commands¶

A Unix command is a command that refers to an actual file on disk.

There is a /bin/ls file, but there is no file for cd.

Example commands to consider:

which cat which cd which ls which afni

1.2.1. cat¶

display file contents in terminal window

The cat command, short for catenate, is meant to dump all files on the command line to the terminal window.

Examples:

cat AFNI_data6/FT_analysis/s01.ap.simple cat here are four files cat here are four files | wc -l

See also

man cat

1.2.2. gedit¶

a text editor for the GNOME Desktop

The gedit program is a graphical text editor that works well across many Unix-like platforms. If you are not sure which editor to use, gedit is a good option. It often needs to be explicitely installed.

Examples:

gedit gedit my_script.txt gedit output.proc.subjFT.txt

If gedit is not installed, one can ask AFNI to choose an editor using

afni_open -e, e.g.:

afni_open -e my_script.txt

See also

1.2.3. less¶

a text file viewer

rcr - add this

1.2.4. ls¶

list directory contents

The ‘ls’ command lists the contents of either the current directory or the directories listed on the command line. For files listed on the command line, it just lists them.

Multiple directories may be listed, in which case each directory is shows one by one.

Examples:

ls ls $HOME ls AFNI_data6/afni ls AFNI_data6/afni AFNI_data6/FT_analysis/FT ~ ls -al ls -ltr ls -ltr ~ ls -lSr dir.with.big.filesCommon options:

-a : list all files/directories, including those starting with '.' -l : use the long format, which includes: type, permissions, ownership, size, date (may vary per OS) -t : sort by time (modification time) -r : reverse sort order -S : sort by size of file (e.g. 'ls -lSr')

See also

man ls

1.2.5. pwd¶

display the Present Working Directory

The pwd command just shows the present working directory.

Examples:

pwd

See also

man pwd

1.2.6. tcsh¶

t-shell

This shell (user command-line interface) is an expanded c-shell, with syntax akin to the C programming language. One can start a new tcsh shell by running this command, or one can tell the shell to interpret a script.

Examples:

tcsh tcsh my.script.txt tcsh -xef proc.subj1234 |& tee output.proc.subj1234

See also

man tcsh

1.3. Special characters¶

Special characters and keystrokes (get extra help from a Unix book)

See also

man tcsh

man bash

a Unix book

Special characters refer to those that have special functions when used in tcsh command or scripts. Special keystrokes refer to those that apply to a terminal window shell with sub-processes.

1.3.1. &¶

run some command in the background

Putting a trailing & after a command will have it run in the background, akin to omitting it and typing ctrl-z followed by bg.

Examples:

suma -spec subj_lh.spec -sv SurfVol+orig & tcsh run.my.script &

Some other uses for & include conditional (&&) and bitwise ANDs (&), as well as piping (|&) and redirection (>&) of stderr (standard error).

See also

1.3.2. \¶

line continuation (or escaping)

Putting a trailing \ at the end of a command line tells the shell that the command continues on the next line. This could continue for many lines.

Examples:

echo this is all one long \ command, extending over \ three linesNote that the latter two lines were indented only to clarify that echo was the actual command name, while the other text items were just parameters.

Another use is to tell the shell not to interpret a special character or an alias.

More examples:

ls $HOME ls \$HOME echo * echo \* ls \ls

Some programs allow for a similar interpretation (and other interpretations).

1.3.3. #¶

pound/hash character: apply as comment or return list length

The pound character has 2 main uses in a t-shell script, to start a comment or to return the length of an array.

In a shell script, if # is not hidden from the shell (in quotes or

escaped with \), then from that character onward is ignored by the

shell, as if it were not there. The point of this is to allow one to

add comments to a script: text that merely tells a reader what the

script is intending to do.

For example, if a t-shell script had these lines:

set greeting = pineapple # check whether user wants to say "hi" or "hello" if ( $greeting == hi ) then # the short greeting echo hi there else echo hello there # this is a strange place for a comment endif

Then the “check whether user wants” line does not affect the script, nor does the comment “this is a strange place for a comment”.

The output is simply, “hello there”.

Note

Pound characters entered at the command line are not treated as comments, they are treated as any other simple text (possibly because the shell authors did not see any reason why one might want comments at the command line, such as for when cutting and pasting scripts).

Another use of # is to get the length of a shell array variable, such

as $path. For example:

echo my path has $#path directories in it

echo the full list is: $path

.. note:: this use does not apply to environment variables, such as

$PATH

1.3.4. '¶

single quotes

Enclosing text in single quotes tells the shell not to interpret (most of) the enclosed special characters. This is particularly important for cases where special characters need to be passed to a given program, rather than being interpreted by the shell.

With respect to scripting, the most important difference between

single and double quotes is for enclosed $ characters, such as

with $HOME, $3 or something like $value. Such variable

expansions would occur within double quotes, but not within single

quotes.

Note

back quotes

`are very different from single'or double"quotesExamples:

3dcalc -a r+orig'[2]' -expr 'atanh(a)' -prefix z awk '{print $3}' some.file.txt echo 'my home directory is $HOME'The first example uses 3dcalc to convert a volume of r-value (correlation values) via the inverse hyperbolic tangent function (a.k.a. Fisher’s z-transformation). The first set of quotes around

[2]hide the[]characters from the shell passing them on to 3dcalc. Then the 3dcalc program knows to read in only volume #2, ignoring volumes 0, 1 and anything after 2.If the

[]characters were not protected by the quotes, it would likely lead to a “No match” error from the shell, since the square brackets are used for wildcard file matching.Alternatively, the quotes could alter go around the entire

r+orig[2].The quotes around

atanh(a)are to hide the()characters, again so that 3dcalc sees that entire expression.The second example hides both the

{}and$characters. Note that$is most commonly used to access variable values, such as in$HOME.The third example just clarifies that shell variables are not expanded, since the output shows

$HOMEand not/home/rickr, for example.

See also

1.3.5. "¶

double quotes

Enclosing text in double quotes tells the shell not to interpret some of the enclosed special characters, but not as many as with single quotes. This is particularly important for cases where special characters need to be passed to a given program, rather than being interpreted by the shell.

With respect to scripting, the most important difference between

single and double quotes is for enclosed $ characters, such as

with $HOME, $3 or something like $value. Such variable

expansions would occur within double quotes, but not within single

quotes.

Note

back quotes

`are very different from single'or double"quotesExamples:

3dcalc -a r+orig"[$index]" -expr "atanh(a)" -prefix z echo "my home directory is $HOME"These examples just demonstrate use of variables within double quotes. The first one uses

$indexas a sub-brick selector with AFNI’s 3dcalc program. In this case,$indexmight expand to 2, as in the example using single quotes.The second example (with

$HOME) is similar to the one with single quotes. But the double quote output shows$HOMEexpanded to the home directory (e.g. /home/rickr), while the single quotes output does not (it still shows$HOME).

See also

1.3.6. `¶

back quotes

Back quotes are very different from single or double quotes. While single and double quotes are commonly used for hiding special characters from the shell, back quotes are used for command expansion.

When putting back quotes around some text, the shell replaces the quoted text with the output of running the enclosed command. Examples will make it more clear.

Examples:

echo my afni program is here: `which afni` count -digits 2 1 6 set runs = "`count -digits 2 1 6`" echo there are $#runs runs, indexed as: $runs set runs = ( `count -digits 2 1 6` ) echo there are $#runs runs, indexed as: $runsThe first example runs the command

which afni, and puts the result back into the echo command. Assuming afni is at/home/rickr/abin/afni, the first command is as if one typed the command:

echo my afni program is here: /home/rickr/abin/afniThe second example line (

count -digits 2 1 6) simply shows the output from the AFNIcountprogram, zero-padded 2 digit numbers from 1 to 6.The third line captures that output into a variable. Going off on a small tangent, that output is stored as a single value (because of the double quotes).

The fourth line displays that output in the terminal window. In this case, the

$runsvariable has only 1 (string) value, with spaces between the 6 run numbers.The fifth line (again with

set runs) sets the$runvariable using parentheses, storing the output as a list (an array) of 6 values).The final

echoline shows the same output as the previousecholine, except that now it shows that there are indeed 6 runs.

See also

man tcsh

1.3.7. ctrl-c¶

terminate a running process (in the current terminal window)

The ctrl-c (while holding the control key down, press c) keystroke is used to terminate the foreground process in the current shell (by sending it a SIGINT signal). It is similar to ctrl-z, but rather than suspending a process, ctrl-c terminates it.

This might be useful when running a shell script that would take a while to complete. Maybe you decide to make a change, or error messages start coming out. If that script is running in the foreground, entering ctrl-c should terminate it.

Example:

1. run 'ccalc' (the prompt is now waiting for an input expression to evaluate) 2. type 3+5 and hit <Enter> (it should show the result: Z = 8) 3. terminate the program with ctrl-c (the prompt should now be back)

See also

1.3.8. ctrl-z¶

suspend a running process

The ctrl-z (while holding the control key down, press z) keystroke is used to suspend the foreground process in the current shell. The process still exists, but will not run while in the suspended state.

This keystroke is often followed by bg (background: a built-in

shell command), to put the newly suspended process in the background.

Alternatively, it could be followed by fg (foreground: a build-in

shell command), to put the suspended process back in the foreground,

as it was in the first place.

Example:

ccalc 3+5 - should show the result Z = 8 ctrl-z - process 'Suspended', prompt should be back ls - works, can type other commands jobs - shows that 'ccalc' is still suspended fg - put 'ccalc' back in the foreground 3-4 - should show the result Z = -1 quit - quit ccalc program

See also

todo:

rcr - consider adding any of these over time...

*, ?, [], !, |, :, ~, %, (, {, <, >, <<, >>